What is it?

For the second model in this series on predicting NFL game outcomes, we’ll look at the Implied Vegas Model (IVM) proposed by thedatajocks.com[1]. The thesis of this model is that the Vegas Model is one of the most consistently accurate models around and its spreads can be used to infer individual team values. For example, if:

The Ravens are favored by 4 points over the Jets

The Jets are favored by 2 points over the Panthers

We can infer that the Ravens should be 6 points better than the Panthers.

Why is it Cool?

By using all the Vegas spreads over a period of time, we can infer the relative ratings for each team. This allows us to concoct our own spreads for unplayed games and make predictions.

To continue the example above, the three teams should have the following ratings

Ravens +6

Jets +2

Panthers +0

This may seem wacky idea but the results are actually impressive. Over the 2003 - 2023 seasons, this model matches the Elo Model’s accuracy (from my previous post) at ~64%!

The Model

Data Sources

Much like the Elo Model, the IVM requires very little data — all you need is the matchup metadata and the Vegas closing-line spread for each game. And luckily, the dataset acquired via nflfastR[3][4] for the Elo Model includes all the info! Like last time, we’ll be considering the 2003 - 2023 seasons.

Setup

This model is quite simple. Essentially, you need to set up a linear system of equations in the form Ax = b where each row is a matchup like:

xhome team - xaway team = spread - HFA (home field advantage)

To set this up in matrix form:

A is a sparse matrix where each row represents a matchup.

1 is assigned in column of home team

-1 is assigned in column of away team

The rows of A are populated with a 21-day window of matchups

21 days was determined by testing to provide the best overall accuracy. It allows some, but not too much, past information to be incorporated into the model. It allows for the best tradeoff between a team’s long-term pedigree and the short-term fluctuations of a season (ex: injuries, team improvement / regression, etc.).

b is the result vector: spread - HFA

If you’re interested, see the Appendix for a discussion on calculating home field advantage

x is the team-ratings / solution vector

Once the matrix equations are set up, all you have to do is solve for x. But we don’t just solve for x in the traditional fashion from your Linear Algebra course (x = A\b for those of you who know Matlab) because the system of equations is obviously over-constrained. We therefore have to estimate the solution using the Moore-Penrose pseudo-inverse. But once we do that we that, we have the team ratings for the games immediately after the data-window considered!

Finer Points

When creating this model, the ratings are determine on a rolling 21-day window. The ratings vector for each window is assigned to each next game, so there is no look-ahead bias.

Also, be aware that these ratings are relative to the time period considered due to the over-constrained situation. I.e., it isn’t relevant to compare ratings from one season to another.

The Results

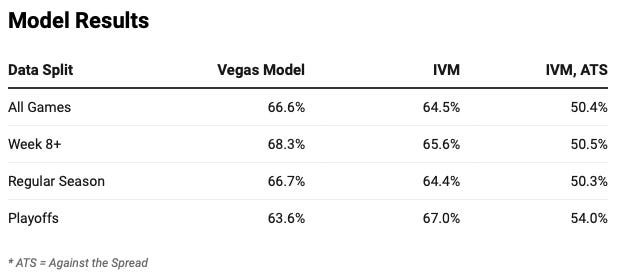

We’ll get right to the results in the table below.

You can see that the IVM has approximately the same accuracy as the Elo Model — ~50% ATS and 64.5% overall accuracy.

What’s really interesting is that this model significantly out-performs the Vegas Model in the Playoffs — ~54% ATS and 67% overall accuracy. The playoffs are certainly a smaller sample size, 239 vs 5,278, but with >200 games, I feel that this isn’t just small-sample bias. To tease this out further, I took a look at season-by-season versions of its playoff performance. Although the performance for each post-season is highly variable (up to 40% swings YoY), it consistently outperforms the Vegas Model, which makes me confident it’s advantage is legitimate:

For overall accuracy: IVM >= VM in 76.2% of post-seasons (16 of 21 seasons)

For ATS: IVM is >50% ATS in 61.9% of post-seasons (13 of 21 seasons)

The Final Dive

In this post, we were able to recreate the Implied Vegas Model proposed by the Data Jocks blog and show that it has comparable performance to the Elo Model from the last post. Surprisingly, this model excels in the Playoffs as evidenced by its outperformance of the gold standard of the Vegas Model.

To squeeze even more juice from this model, in the future I’d like to try including the starting quarterback into the coefficient matrix (A). That way I can infer not only the quarterback’s implied value but also how much of the team’s implied value is due to the quarterback. For example, if the Chiefs have a +6 rating with Patrick Mahomes and +2 without him, we can infer that Mahomes has a value of +4. But actually implementing this will be tricky — the number of instances where this can be inferred are probably few.

Well that’s all for now! Next time we’ll be leaving our protected lagoon of model replication and swimming into the open ocean with an original model I’ve cooked up. See you then!

Appendix

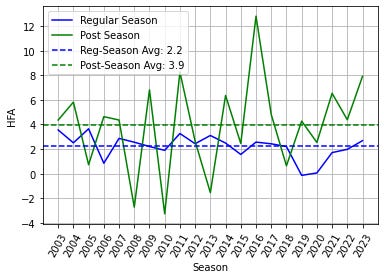

To compute the value of home-field advantage (HFA), you just need to find the mean point differential for home teams and then divide it by two. Because there are many games, the strength and circumstances of all the matchups are randomized so we can be reasonably certain we’re measuring the effect of playing at home.

I did this calculation season-by-season for both the regular season and the playoffs. That way, I can see how stable HFA is over time & if it’s appropriate to only have one number in my model. From the chart below, you can see that regular-season HFA is quite stable at approx. +2.2 points, so I was able to keep things simple & only have one HFA value in my model.

Conversely, playoff HFA proved a bit more interesting:

Playoff HFA is highly variable due to the small number of games.

Playoff HFA is higher than regular-season HFA, but this is a red herring. What’s actually going on is that because of playoff-seeding, the home team is almost always the stronger of the two teams, and therefore should be winning more often and by more points. We don’t have the natural home-away mixing that happens in the regular season.

Because this +3.9 playoff HFA can’t be relied upon, it opened me up to experiment!

Through this experiment, I found that +1.1 HFA for the playoffs was the sweet spot.